By Megan Pacheco, Executive Director of Challenge Success

Offering mental health interventions at school isn’t enough – we must work upstream.

The CDC recently released a list of six school-based strategies that, “can help prevent mental health problems and promote positive behavioral and mental health of students.” While we agree these are important components for addressing youth mental health, we believe more is needed to address root causes. We aren’t going to fix the youth mental health crisis only by teaching kids mental health literacy, mindfulness, and healthy coping skills.

Yes, we need on-site mental health services. But we’re letting ourselves off the hook if we don’t acknowledge and address the inherently flawed system. While we support all of the strategies proposed by the CDC, we believe even more is needed to address some of the root causes of the problem. As the stewards of young people’s development, it is our responsibility to go beyond teaching them how to be resilient; we need to work with them to change the system that necessitates these skills.

What if we allowed ourselves to recognize the root causes of the distress our youth are facing? What if we diagnosed the system itself?

By emphasizing academic achievement at all costs, school environments may unintentionally harm students – especially those who have been historically marginalized. Based on our years of research and experience partnering with schools across the country, here are three strategies we recommend for transforming the student experience to more effectively meet the mental health needs of your students.

Redefine the purpose of school

Our culture’s overemphasis on grades, test scores, and rankings is often in opposition to fostering students’ well-being, engagement, and belonging in school, leading to unhealthy levels of stress. As W. Edwards Deming recognized, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” Whether intentional or not, we’ve designed a system that prioritizes extrinsic measures of success over student learning and well-being.

At the root, there is a disconnect between what adults (policymakers, parents, caregivers, educators) say they value and what young people perceive society values. While adults often define success in the real world as including well-being, supportive relationships, joy, purpose, and financial security, the message students often receive is that society values high grades, prestigious colleges, and high income above all else.

By emphasizing academic achievement at all costs school environments may unintentionally harm students – especially those who have been historically marginalized. We must instead create school systems that center growth, learning, and engagement.

Yes, this is a big ask. But here are three things you can do in your school right now:

- Expand our definitions of success: Reaching milestones, demonstrating your learning, and overcoming obstacles tell a much richer story than class rankings, college acceptances, and SAT/ACT scores alone. (We also need to work with higher ed on the admissions process, but that’s a topic for another day.)

- Stop measuring student “success” with inequitable measurement tools: The “achievement gap” is a wolf in sheep’s clothing that doesn’t address the reasons students from low-income communities don’t measure up like their more affluent peers. Consider alternative forms of assessment such as competency-based records and performance-based assessments.

- Stop linking student achievement to teacher performance: The teachers are not the problem, the system is. Release them from the pressure of teaching to the test and provide them with professional development around deeper learning, cultivating climates of care, and culturally-sustaining pedagogy.

Rebuild the school schedule to meet developmental needs

It’s time to rethink outdated constructs that have created artificial constraints on the school day. The current model goes against what we know about learning and child/adolescent development. Providing longer class times for deep learning, time built into the schedule for building connections and relationships, and opportunities for autonomy will support students’ well-being, engagement, and belonging in school.

Here’s why these three areas matter:

- Sleep: Middle and high school students need 8-10 hours of sleep per night. It’s not merely that they can benefit from it, or their academic performance will increase (which it will). Their growing bodies actually require it. When we talk about childrens’ health, sleep should be up there with nutrition and exercise, not a nice to have.

- Time for connection: Because we know that student-teacher relationships are absolutely crucial for well-being in school and serve as a protective factor outside of school, we can create pockets of time within the school day for relationship building. Rather than viewing connection activities as “taking away” from instructional time, we might view them as the prerequisite for engaged learning.

- Longer blocks for deeper learning: Learning centered on achieving mastery requires reflection, opportunities for questions, and varied modalities of instruction and learning. Typical class periods often deprioritize these aspects and prevent students from engaging deeply in their work.

Don’t get me wrong, redesigning school schedules is extremely complicated. There’s a whole list of things to consider like transportation, teacher contracts, families’ work schedules, and more. But we have brilliance in our midst and we can figure it out. Let’s put our heads together and solve it.

Related: How to use the school schedule to support greater connection and balance

Recognize the elephant in the room

The educational system in the US was designed to be inequitable, but it’s uncomfortable to talk about this and can feel daunting to tackle. However, if we don’t intentionally address equity in our approach to the youth mental health crisis, we aren’t going to be able to make much progress.

Here are three things that are within our sphere of control:

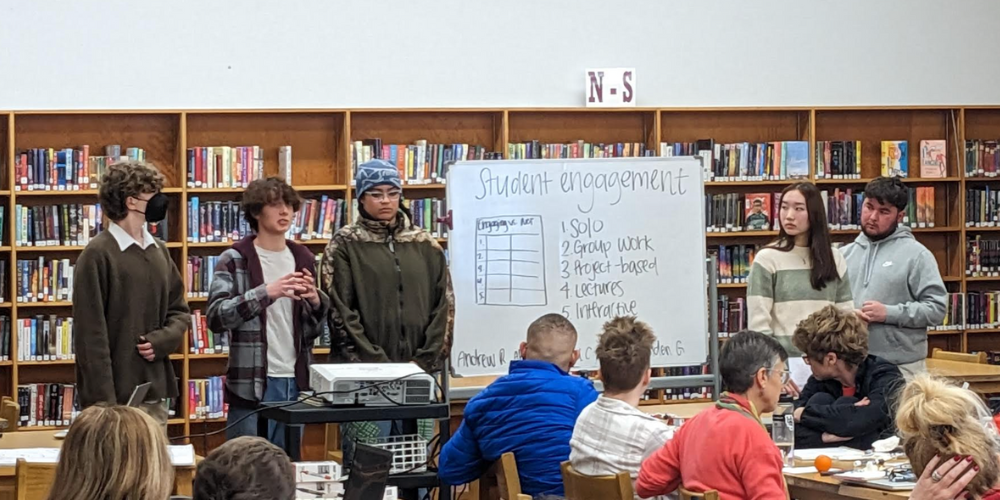

- Center the student experience in your decision-making: Don’t guess about what will work for them – ask them. Student voice should be central to the conversation, not an afterthought. Our goal should be to build a deeper awareness of the student experience, especially those for whom identity, culture, or socioeconomic status has resulted in barriers to access and success.

- Leverage unique community assets by co-designing with community members: Instead of designing for them, co-design with them and then focus on systemic changes based on the evidence of what works in that local context.

- Use the most recent research: This research can help you build an increased understanding of the current environmental conditions that cultivate well-being, belonging and engagement in schools. What’s that saying, “when you know better, do better,”? Now we know, and it’s time to act.

In closing, we want to be clear that this is not a criticism of the CDC, schools, districts, or any individual person. As a culture, it is often our inclination to put the onus on the individual rather than the system. While there is certainly an opportunity to support students in learning healthy coping skills, addressing the root causes of student distress, disengagement, and lack of belonging through preventative strategies is just as important to solve these pervasive issues.

Megan Pacheco is the Executive Director for Challenge Success. The nonprofit – affiliated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education – elevates student voice and implements research-based, equity-centered strategies to increase well-being, engagement, and belonging in K-12 schools.